Don Trunkey spent 14 years on the faculty at San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH), the last 8 as the chief of surgery. He was an outspoken, confident, and decisive leader beloved by the staff, faculty, residents, students, and patients because of his warmth, self-deprecating humor, fairness, obvious regard for the opinions of others, and courageous stance to defend “doing the right thing”. He never hesitated to take what he felt was the right and necessary step to improve patient care, even if it was politically unpopular or raised the hackles of someone in power who had a secondary agenda to maintain the status quo or simply save money at the expense of the largely poor or minority patients who relied on SFGH for their care.

After he had completed his surgical residency at the University of California, San Francisco, he spent one year with Dr. Tom Shires at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas doing trauma research on cellular function in shock, then returned to join the faculty at SFGH in 1972. At that time the chief of surgery at SFGH was Dr. F. William Blaisdell, who had been a mentor of Don’s when he was a resident and had played a large role in influencing him to follow his footsteps as a trauma surgeon.

Don established his academic research at SFGH on the pathophysiology of shock under an NIH grant and published extensively on the subject, while focusing his clinical activities on trauma and burns. He had learned a great deal about burn treatment while in Dallas, where the Parkland Burn Center was already established as a national model for care of the burn patient. At SFGH at that time, burn patients were admitted to any surgical bed that was open, not ideal for prevention of infection and management of the patients’ sometimes extensive wounds. They lacked, for example, a (hydration tank) or dedicated procedure room for dressing changes. Don wanted to establish a dedicated burn unit, which Dr. Blaisdell agreed would be a worthwhile and important step in improving their care. Unfortunately, Don discovered that the hospital director was opposed to the idea of a separate burn unit for financial reasons.

Dr. Trunkey nevertheless pressed on, identified some empty ward space, recruited nurses for the unit, found an old bathtub to use, and invited the mayor of San Francisco, Joseph Alioto, to dedicate the “Alioto Burn Center.” Dr. Blaisdell invited the famous chair of surgery at Louisville, Dr. Hiram Polk, to give a talk at the dedication ceremony. City dignitaries were invited. Only on the day of its opening did the hospital director find out about it, but it was already a fait accompli, lauded by the mayor and Director of Public Health, who had found funding for it!

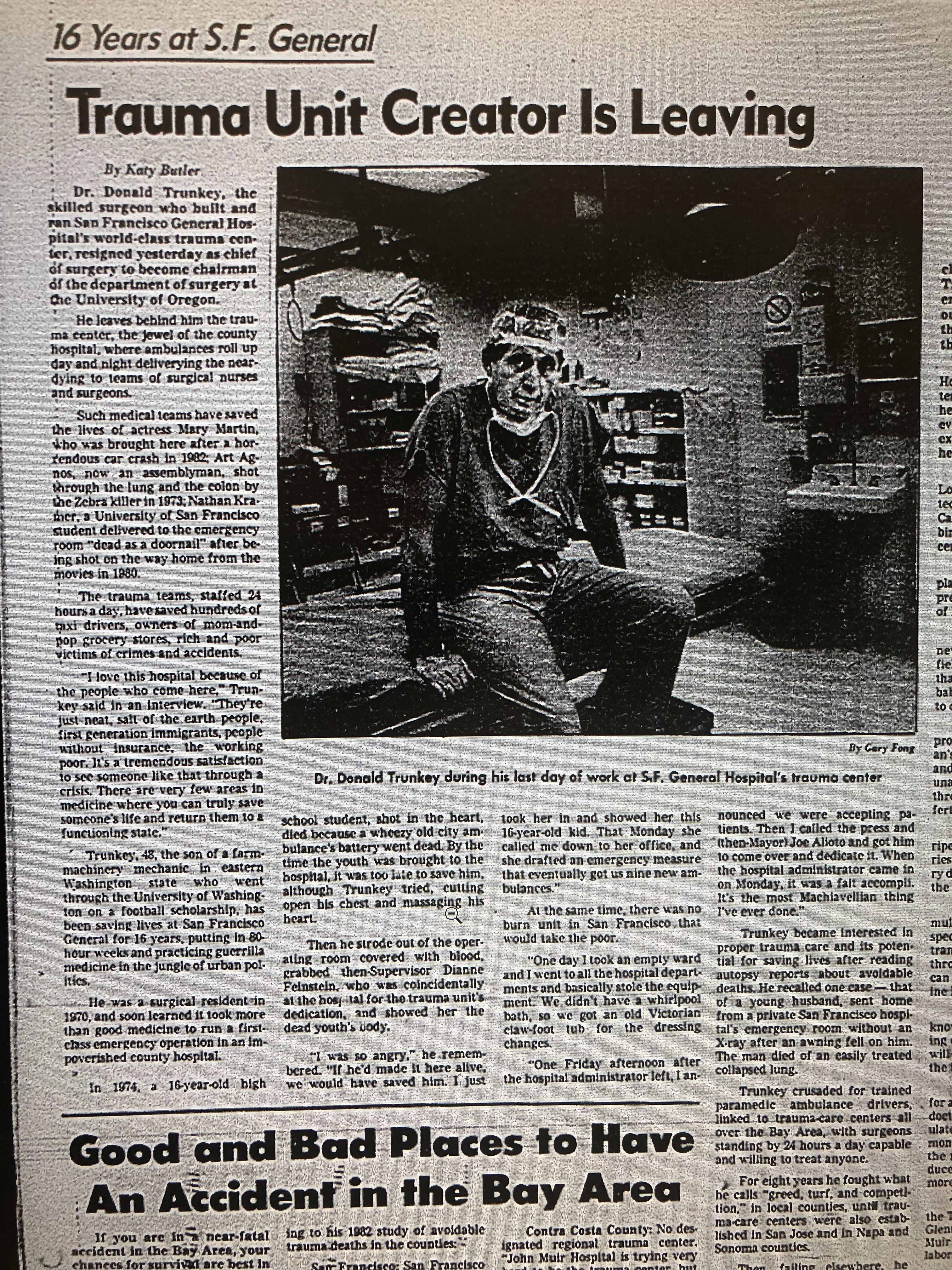

When Dr. Blaisdell left San Francisco in 1978 to assume the chair of surgery at the University of California, Davis, Dr. Trunkey was appointed chief of surgery at SFGH. He served in that capacity for 8 years, until becoming the chair of surgery at the Oregon Health and Science University in 1986. Although he was only 41 when he became the chair of surgery at SFGH, he had already achieved international stature as a trauma surgeon due to his research, his publications, and his larger-than-life persona. Just the year before, he had co-authored a landmark study that demonstrated the superior outcomes of injured patients who were cared for in a trauma center rather than a private community hospital without special expertise in trauma. He became chief just as a property-tax limitation measure, Proposition 13, had been passed in California that severely decreased the funding available for public services, such as supporting a city/county hospital for the poor. Fortunately, SFGH had by then gathered such high regard as THE place to go if you were injured, that it was able to survive as an institution. Its survival was in no small way due to the skill, personality, and great accomplishments of its leader.

Over the next 8 years he solidified the importance of organized systems of care in achieving good outcomes for the injured patient. He and a small cadre of his contemporaries on the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (COT) established the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) system as a mandatory aspect of trauma care and developed a system of certification and verification of hospitals’ ability to manage trauma patients. He served as chair of the COT from 1982 to 1986. He became a director of the American Board of Surgery, President of the Society of University Surgeons, and President of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Although Dr. Trunkey was required by his many national roles and his growing international fame to travel from San Francisco frequently, he assembled a distinguished and highly capable cadre of surgeons at SFGH, each of whom had gained expertise in the broad range of surgical and medical skills needed to provide the highest level of care for the most critically injured and ill of our society. He continued the research program begun under Dr. Blaisdell’s leadership, but expanded it to include more clinical and collaborative research. He developed the Trauma Foundation as a major force in trauma prevention.

By the time Dr. Trunkey left San Francisco for his position in Oregon, SFGH had been firmly established as one of the nation’s foremost trauma centers and its existence was secure. He left an indelible mark on the institution.

Karen Deveney, M.D., F.A.C.S.

The above remarks are drawn from both personal recollection as well as from the excellent account contained in the book, The History of the Surgical Service at San Francisco General Hospital authored by Drs. William Schecter, Robert Lim, George Sheldon, Norman Christensen, and F. William Blaisdell.