To me and to many trauma surgeons around the world, the word “Trunkey” is synonymous with the word “Trauma”. Most of us completing our residencies in surgery in the 1980s never considered trauma surgery as a career……it was just something you did when you were on call for the emergency room.

When I moved to California after finishing my chief year in surgery at the University of Michigan, my plan was to be a pediatric surgeon. But sometime during my first year of pediatric surgery fellowship at Stanford University, I realized that I didn’t actually like that field and was considering other areas of specialization.

Around that same time, the state of California was beginning to organize trauma systems by county, spurred on by the seminal work of Trunkey, West, and Lim demonstrating the high rate of preventable deaths after injury in areas of the state without trauma systems. (1) I decided to visit the Department of Surgery at the San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) to scope things out and had the great privilege of meeting with Trunkey in person.

He told me that I belonged in the trauma world and when I asked him how he knew he replied: “I just noticed how your face lit up when you talked about trauma”! And so, I became a trauma surgeon, making frequent trips to San Francisco to learn from the masters at SFGH while we set up the trauma system in the county of Santa Clara.

Even after Dr. Trunkey moved to the University of Oregon to assume the position of Chair of the Department, he continued to mentor me in both my clinical and my academic endeavors. In 1989, I was offered a position at SFGH under the leadership of Dr. Frank Lewis, only the second woman to be on their faculty after Dr. Muriel Steele.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. Trunkey and I, along with Colonel Don Jenkins (US Air Force, ret.) traveled to Australia where we taught numerous trauma courses from Melbourne to Sydney. Of course, with Trunkey there was always fun mixed in with work. One day, we traveled to the Blue Mountains, the home of many fine Australian wineries.

We stopped at numerous tasting rooms and at every stop Dr. Trunkey would pull out his credit card and join their wine club so that he could have a continuous supply of Australian wine shipped to his home in Portland. But international travel can wreak havoc on your time zones and one morning during a teaching conference in Liverpool (AU) we were both in need of caffeine. We found ourselves in the kitchen of the hospital but no one was there. I decided to brew coffee and must have hit the start button too many times because not only did we fill the first carafe but also the entire floor with coffee! I was mortified of course, but Trunkey just looked at me and responded with his well-known laugh. I don’t think the kitchen staff ever did figure out who spilled all that coffee!

In 2006, we initiated the Senior Visiting Surgeons Program that allowed non-military surgeons to work as volunteers at the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) in Germany. Landstuhl became the evacuation hospital for all wounded US troops from Afghanistan and Iraq.

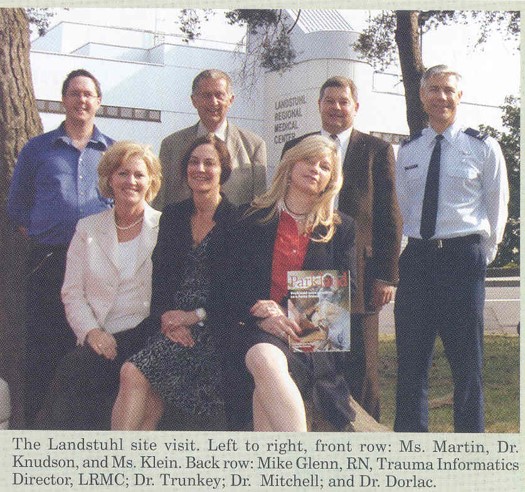

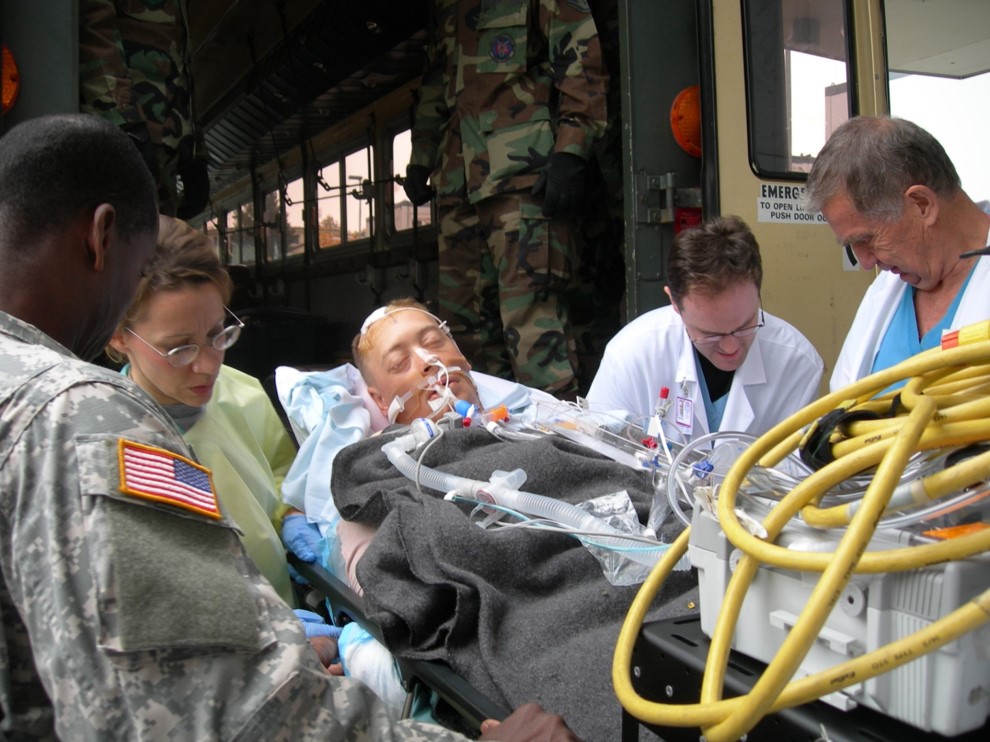

Dr. Trunkey (Col, US Army, ret) was a frequent visitor to LRMC, mentoring young military surgeons in the ICU and operating room, caring for the injured, and assuring that LRMC would pass their inspection by the American College of Surgeons/Committee on Trauma Verification Review Committee (VRC) (a committee he helped to found while he was the COT Chair) to become a level 1 trauma center. (2,3) (See also attached Photos)

I think my very favorite story about Dr. Trunkey occurred in Hawaii. We were both asked to speak at the Hawaiian Trauma Conference and at the conclusion were heading to a traditional Hawaiian luau. We invited Don to my cousin’s home in Oahu and offered to drive him to the party. When the doorbell rang my young twin daughters answered it and then ran to me saying: “Mom there is this really big man out there in a grass skirt”!. Yes, I said, that in a nutshell is Dr. Trunkey.

In many ways, Dr. Trunkey was my professional father. Even my own father (an engineer) knew his name and how important he was to me in my career and to the world of trauma. To me, Trunkey was larger than life and his death (like my own dad’s) leaves a void that will never be filled.

M. Margaret (Peggy) Knudson MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery, University of California San Francisco

Medical Director, Military Health System Strategic Partnership, American College of Surgeons

References

- West JG, Trunkey DD, Lim RC: Systems of Trauma Care: A Study of Two Counties. Arch Surg 1979;114:455-460.

- Moore EE, Knudson, MM, Schwab CW, Trunkey DD, Johannigman JA, Holcomb JB: Military-civilian collaboration in trauma care and the Senior Visiting Surgeon program. NEJM 2007, Dec 27;357:2723-7.

- Knudson MM, Mitchell FL, Johannigman JA: First trauma VRC site visit outside the US: Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (Germany). Bull Am Coll Surg 2007;92:16-19.

Legends for Figures

Figure 1: Dr. Trunkey helping to load an injured soldier onto the bus at Landstuhl for his trip to Ramstein Air Base and the beginning of his journey home.

Figure 2: The COT Verification Review Committee at Landstuhl Germany.