It’s been more than 30 years since Dr. Trunkey saved my younger brother’s life. James was barely 21 when a young man he’d never met before shot him in the neck over a foolish matter. Our local doctor in that small Oklahoma town packed him in an ambulance and sent him to Wichita, Kansas, 60 miles away. He thought the bullet could have hit an artery and that James would need an arteriogram.

He never got one. When James turned 21, My dad’s insurance no longer covered him. The surgeon told James the procedure was too expensive and that he’d send some medical students around to look at him. He’d be fine. He told James it was one of the few bullet wounds that could be taken care of with just a bandage.

A few months later, James, a mechanic, reached up to work on a car that on a lift above him. His arm went numb and he could barely move it. The doctor at the emergency room of the local hospital said it was extremely likely to be related to the gunshot wound. He told James he needed to go see the surgeon who’d seen him in Wichita. That doctor told James to come see him on Monday, three days later. James felt powerless. One doctor said it was outside his expertise and the “expert” said, “See you in three days.”

Three days later James’ arm was horribly swollen. Emergency surgery was performed to remove 11 blood clots from his arm and to repair an aneurysm the size of a hen’s egg on his brachial artery under the collar bone.

Why give all these details about James’ history? To demonstrate the difference between a real doctor and, by my definition of a doctor, a fake. Real doctors can be busy, even gruff, but they respect you. They make sure you get the information you need to make decisions. They always, always try to save your life and THAT always comes first.

I asked James to come stay in San Francisco with me my husband, Lee Henry. He started a job but called soon after starting it to tell me something was wrong. Lee told him to go to San Francisco General Hospital because he had a cousin working there and they accepted patients without insurance.

This is when Don Trunkey saved James’ life. With another surgery on the damaged artery, yes, but there were several more of those in the following years. It was by treating him with kindness and respect. It was by giving James the information he needed no matter how depressing or negative it might be. James’ prognosis was very worrisome, but Dr. Trunkey was honest. He was assigned to James by sheer luck, and James certainly got the best surgeon one could get. Dr. Trunkey successfully operated on James, but he also got down into the weeds about how James got into the predicament he was in. He asked James about seeing the initial angiogram because he saw that as standard treatment and found out there was none.

Some people may not like to hear about medical malpractice lawsuits. I’m sure many are frivolous. But James has suffered through seven major surgeries, including grafts taken from both legs to replace the latest failed repair on his artery. James moved back to Oklahoma and soon needed another repair operation. Dr. Trunkey graciously referred him to a doctor in Dallas he trusted. I know that Dr. Trunkey saw James as a young man who had been harmed by callous disregard. He saw him as a vulnerable young kid who needed care and simply did not get it. The results were years of surgeries and fear of the next one.

James did get a lawyer. He did sue the original doctor who told him an arteriogram was too expensive for a little gunshot wound. After many years he won, in part because of Dr. Trunkey’s testimony that an arteriogram is standard procedure on a case such as James’.

James has gone on to live a full life. He has four children and grandchildren. He loves to fish, he still works as a mechanic, but he will not be able to have another artery repair. The artery is too fragile. He knows from his doctors what the eventuality is. But he’s at peace with that.

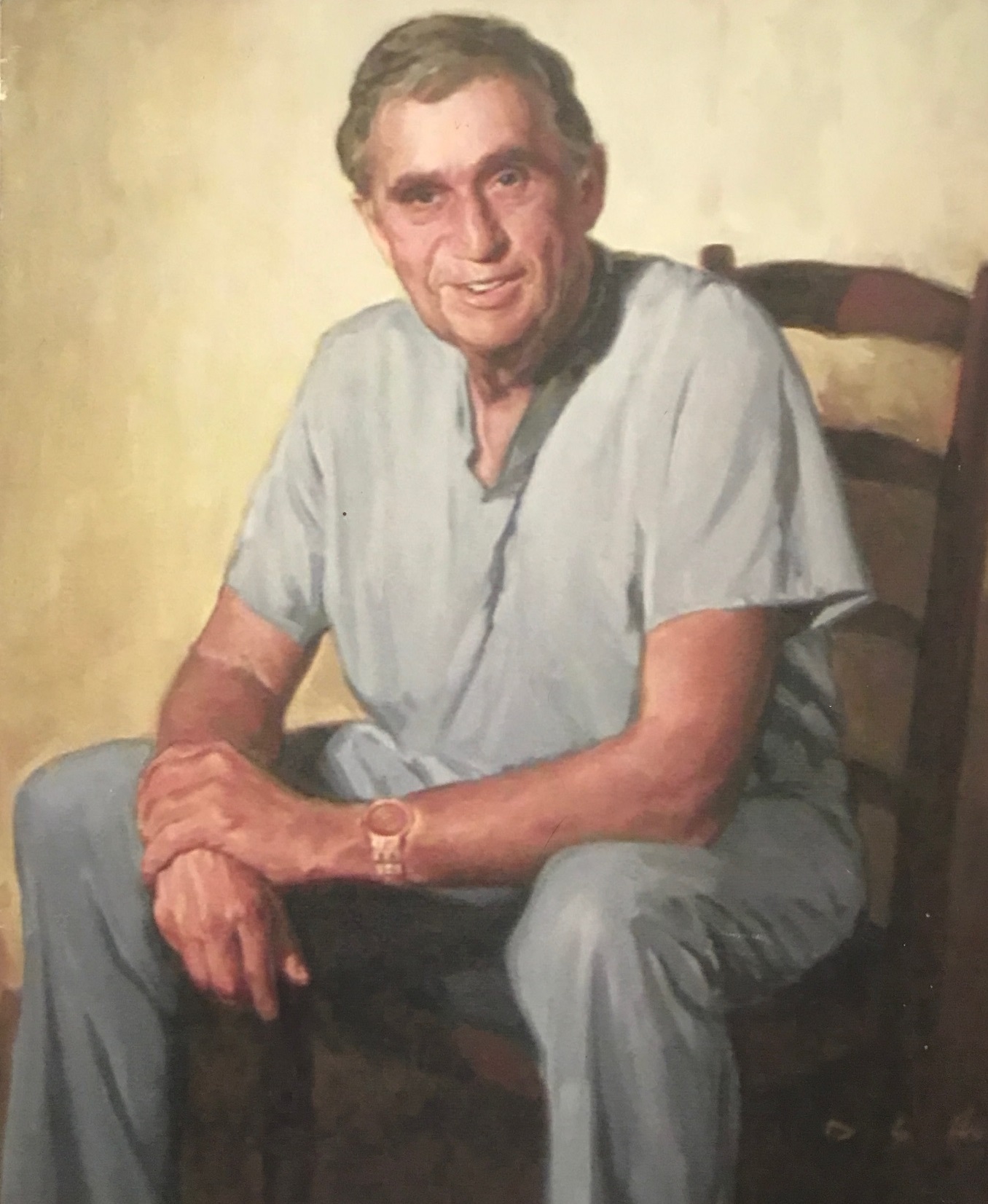

My whole family will always be grateful to Dr. Trunkey, a real doctor. I saw him several years after James left San Francisco at a fancy social affair and he asked me how James was doing. His face showed care and concern. That face that will stay in my memory as long as I live.