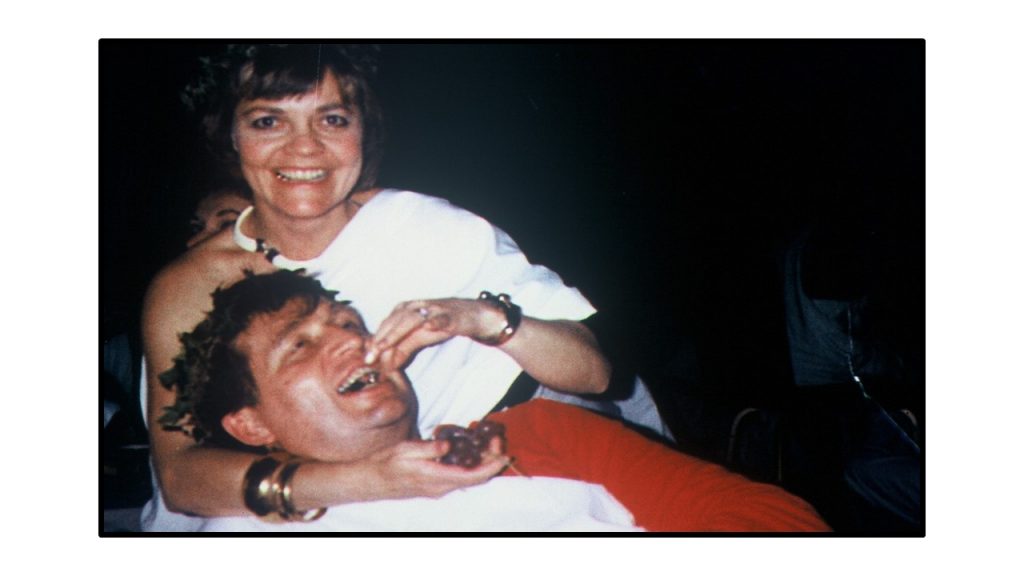

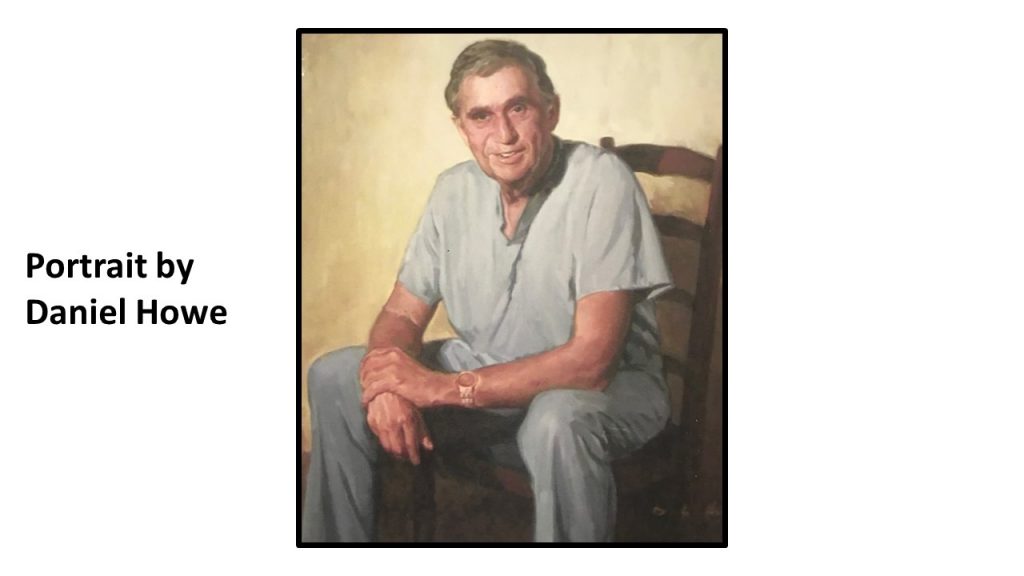

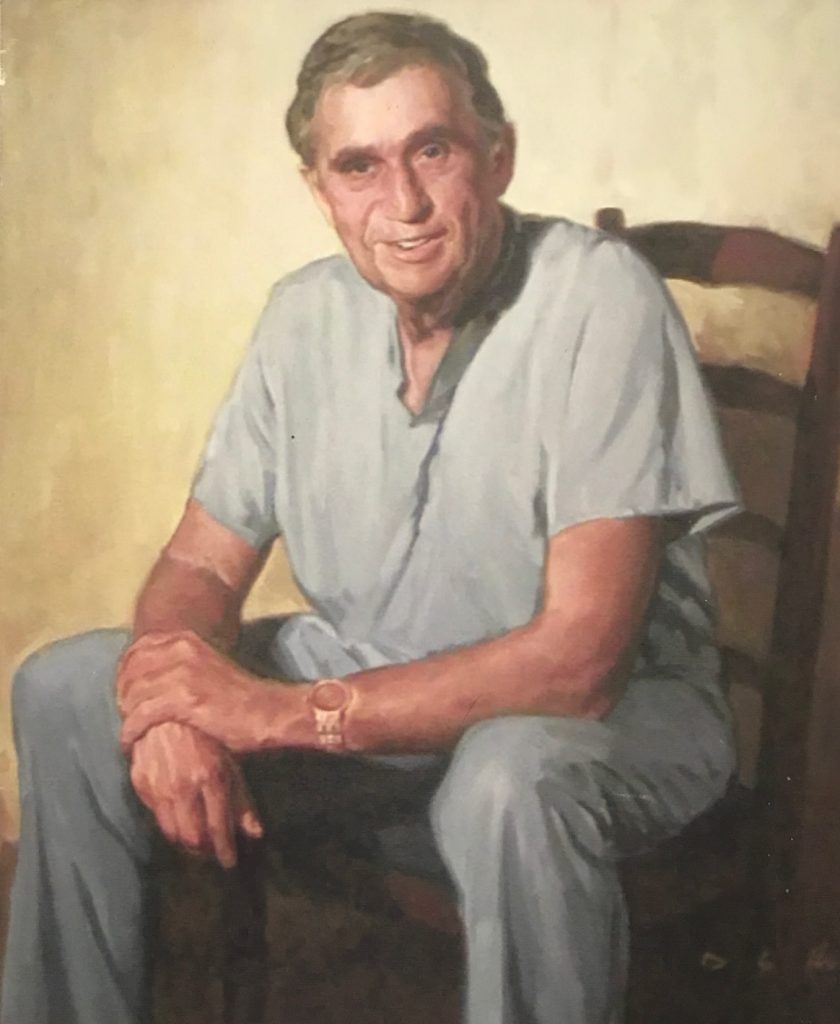

Donald Dean Trunkey, M.D., 81

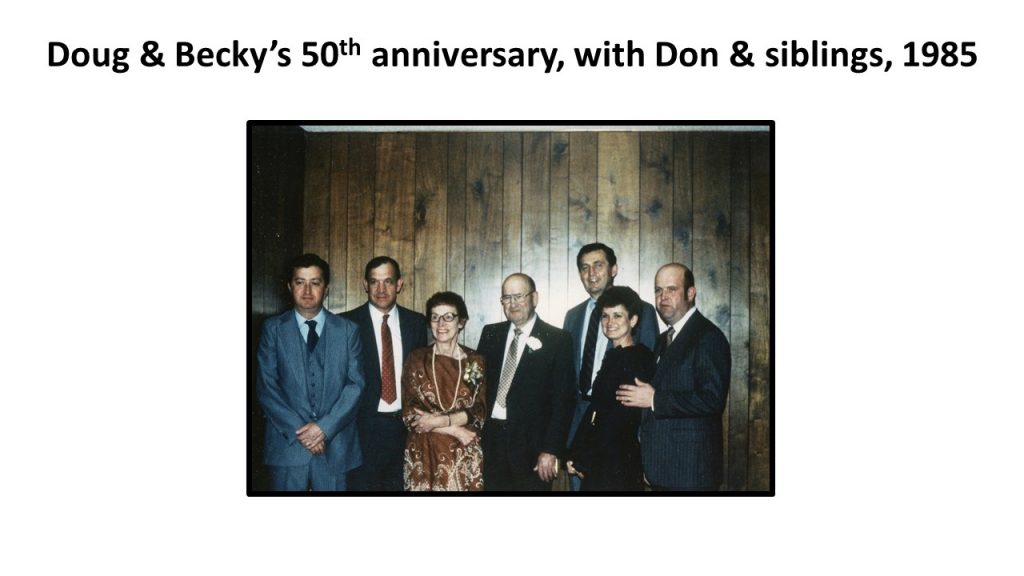

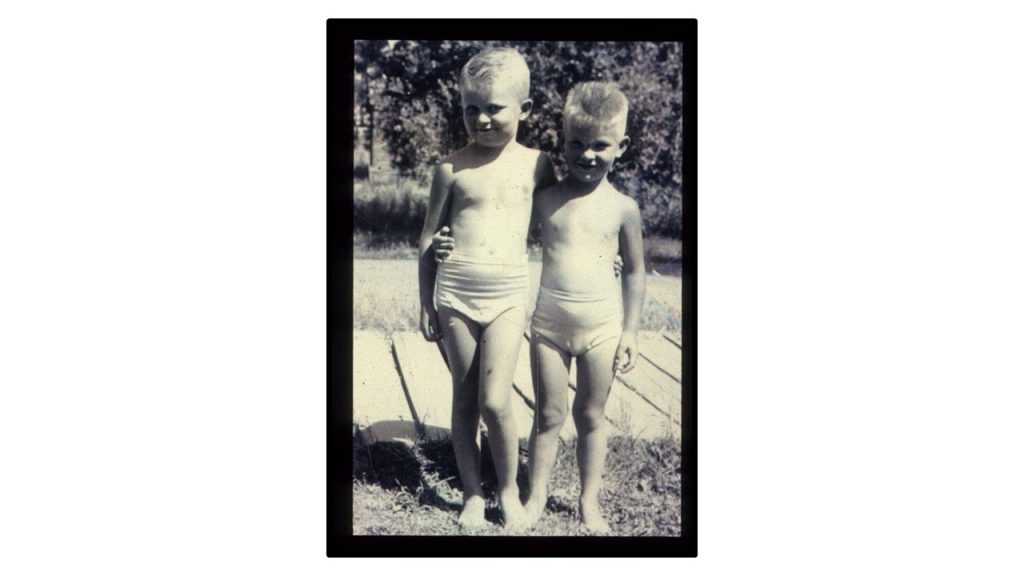

Donald Dean Trunkey passed away peacefully with his loved ones by his side on May 1, 2019, in Post Falls, Idaho. He was born on June 23, 1937, in Oakesdale, Wash., to John Douglas and Rebecca Nelson Trunkey. The family moved to St. John, Wash., where Don grew up and graduated from St. John High School in 1955 as valedictorian. He attended what was then Washington State College and received a degree in zoology, which made him the last person to have graduated from WSC before it officially became Washington State University. He was a member of Alpha Tau Omega.

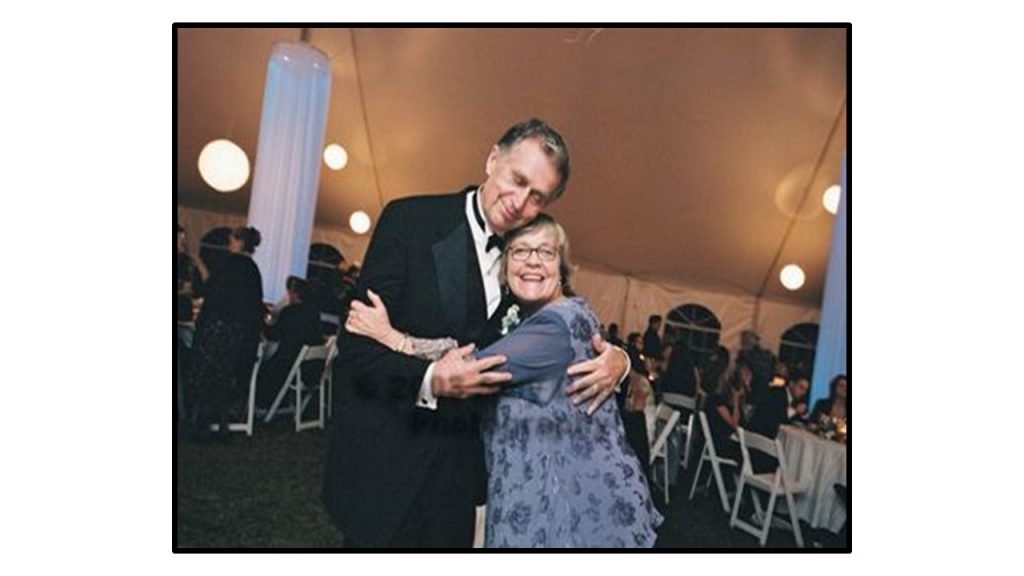

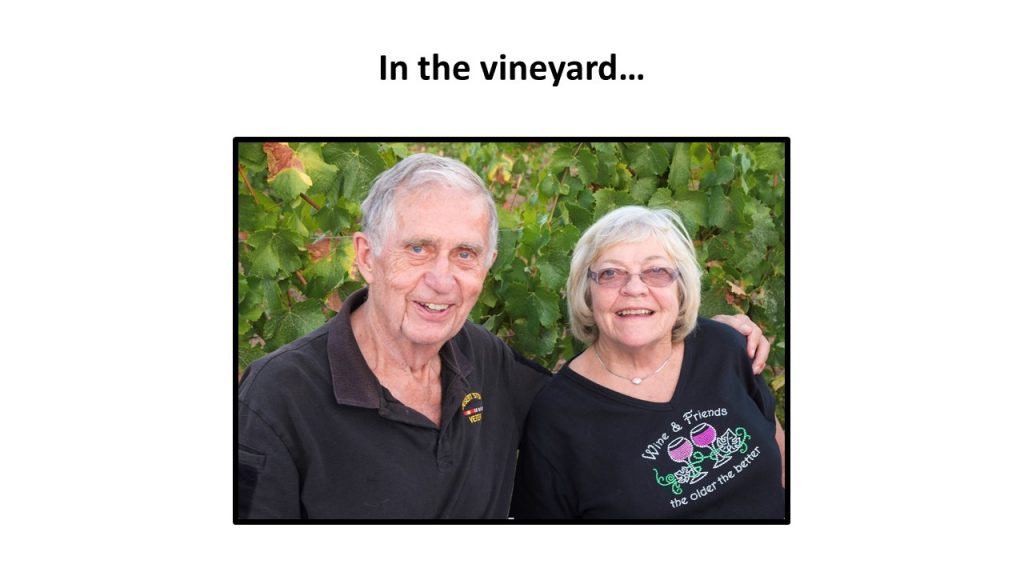

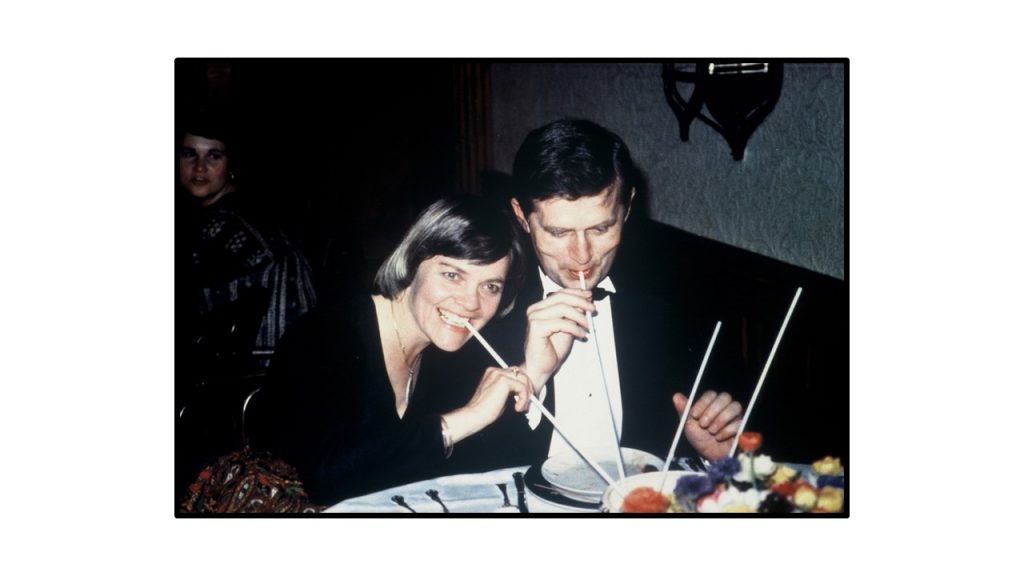

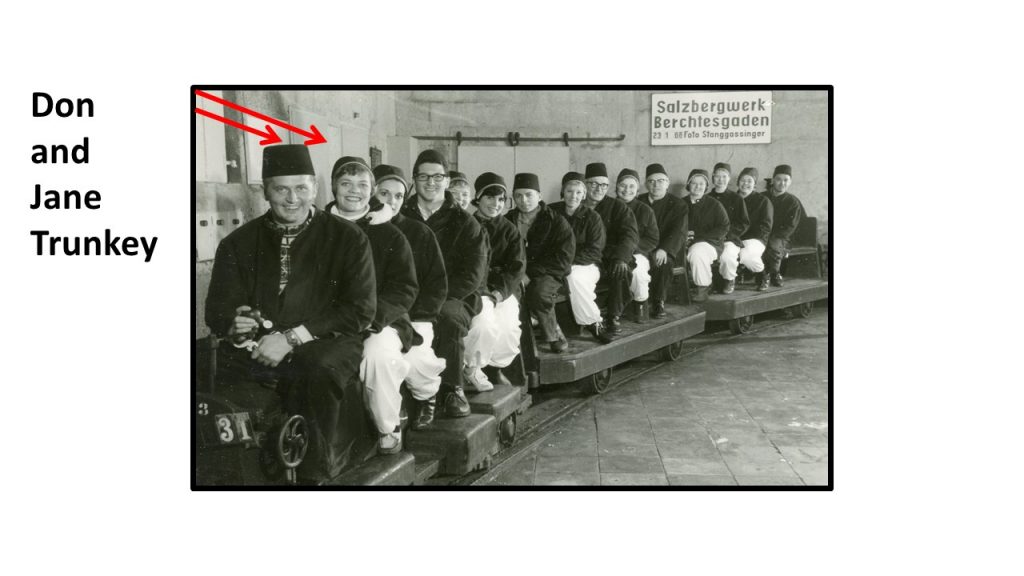

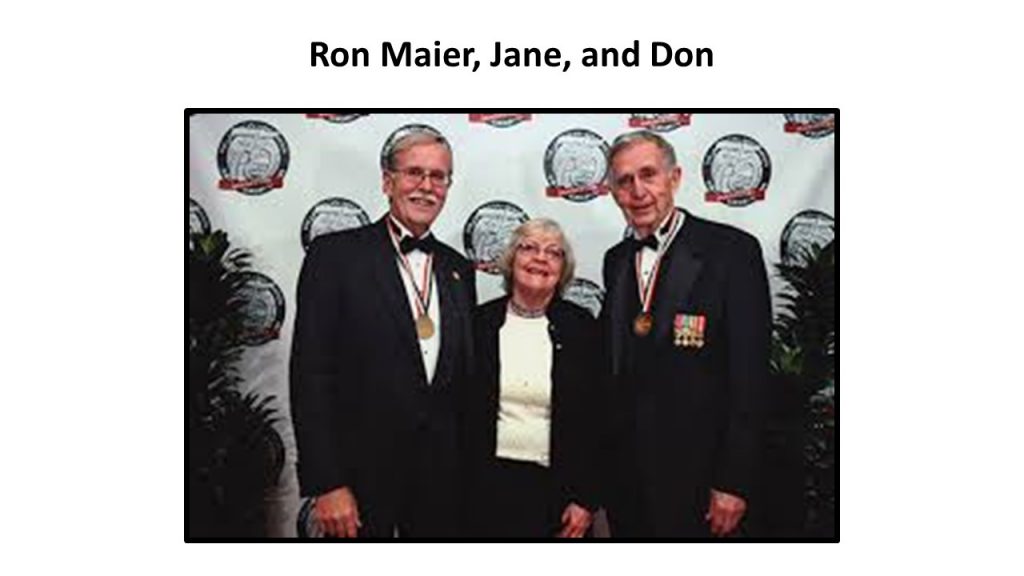

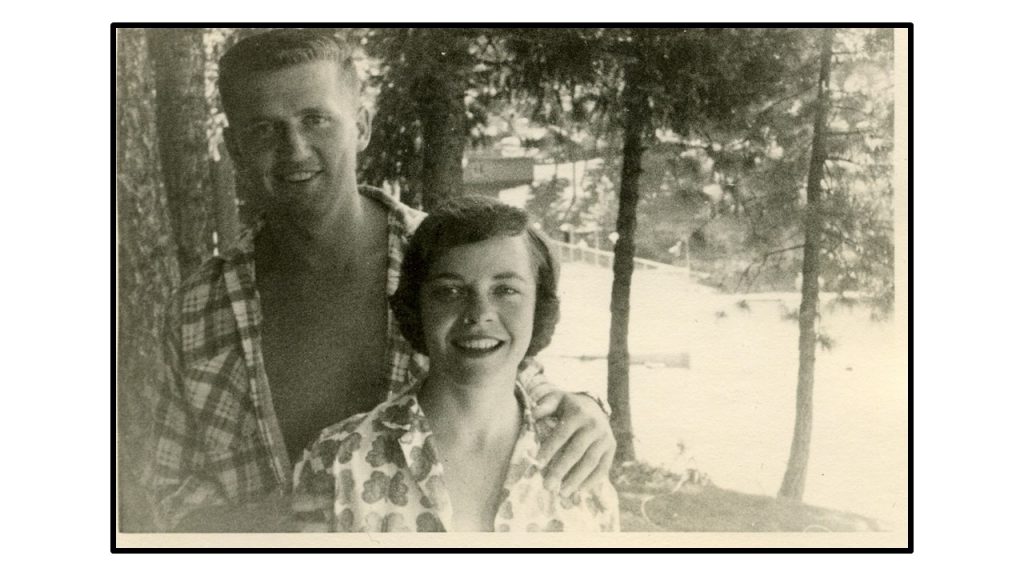

Don and Jane Trunkey were married in Colfax, Wash., on Sept. 26, 1958. After graduation, Don went on to the University of Washington, where he received his doctorate of medicine degree. He did a rotating internship in Portland, Ore., at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

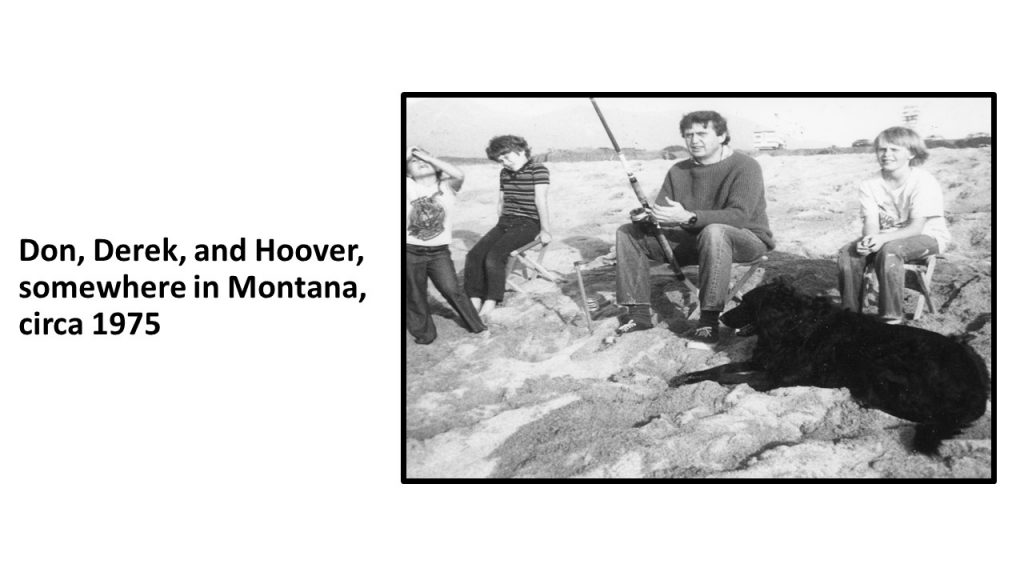

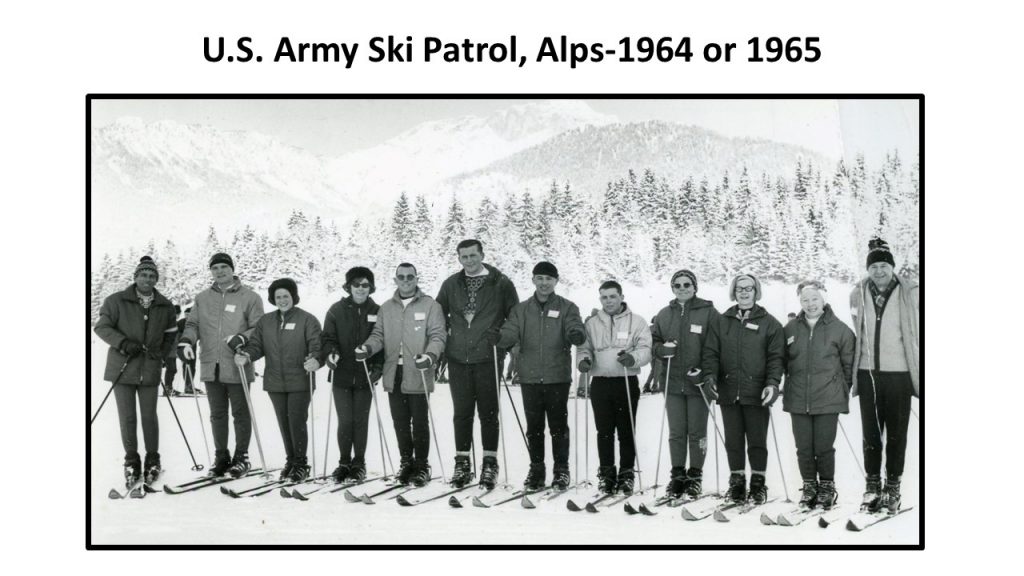

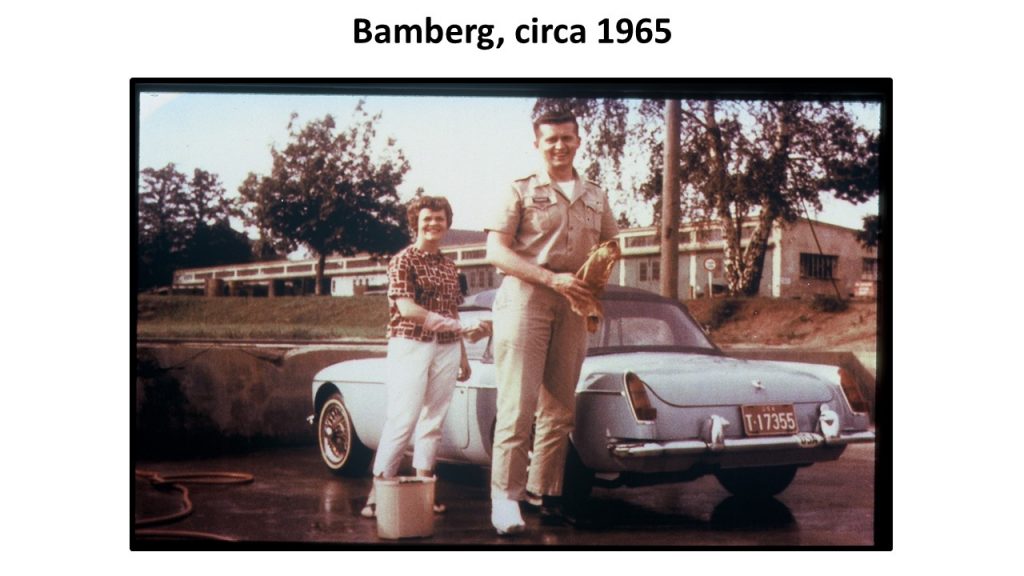

Don later served within the U.S. Army with the 4th Armored Division 2nd Calvary, in Bamberg, Germany, in the dispensary for two years. While there, their son, Robert Derek was born in Nuremberg, Germany; followed four years later by their daughter, Kristina “Kristi” Jo, born in San Francisco, Calif.

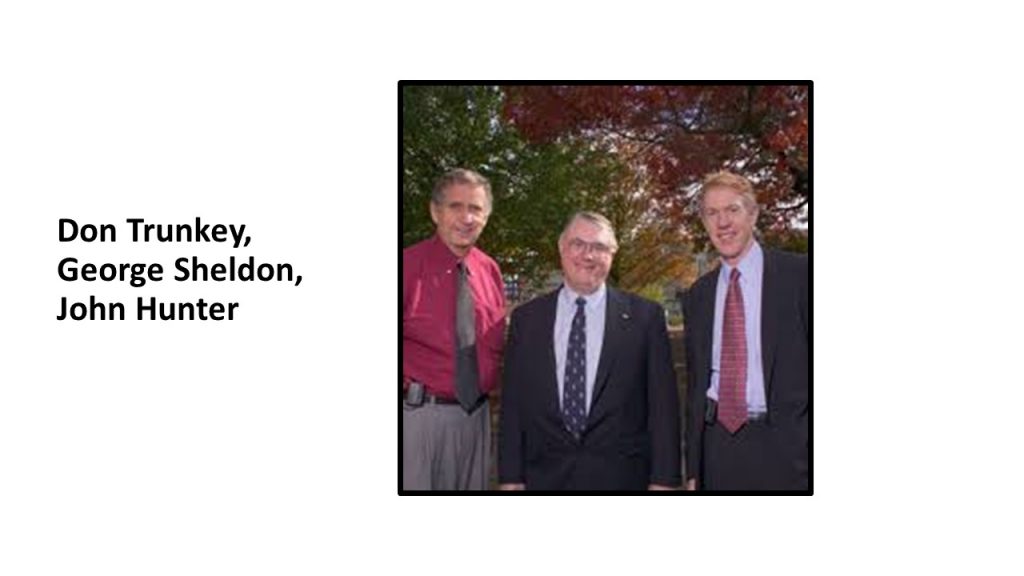

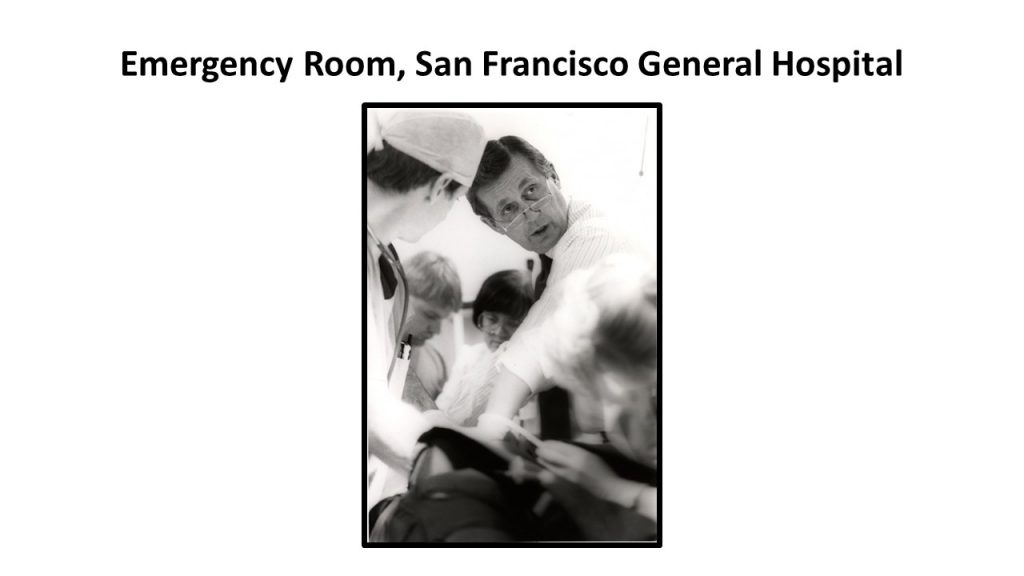

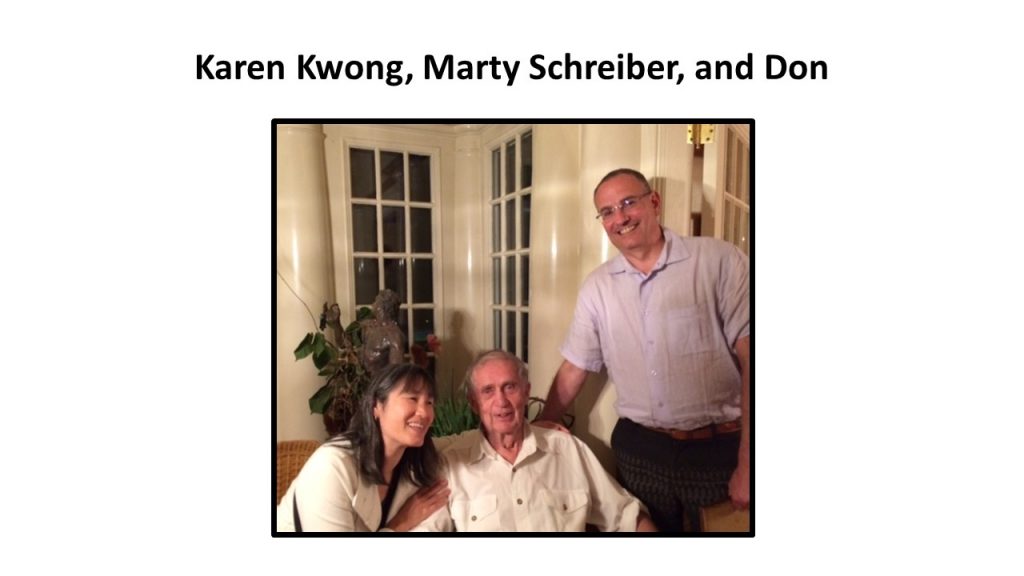

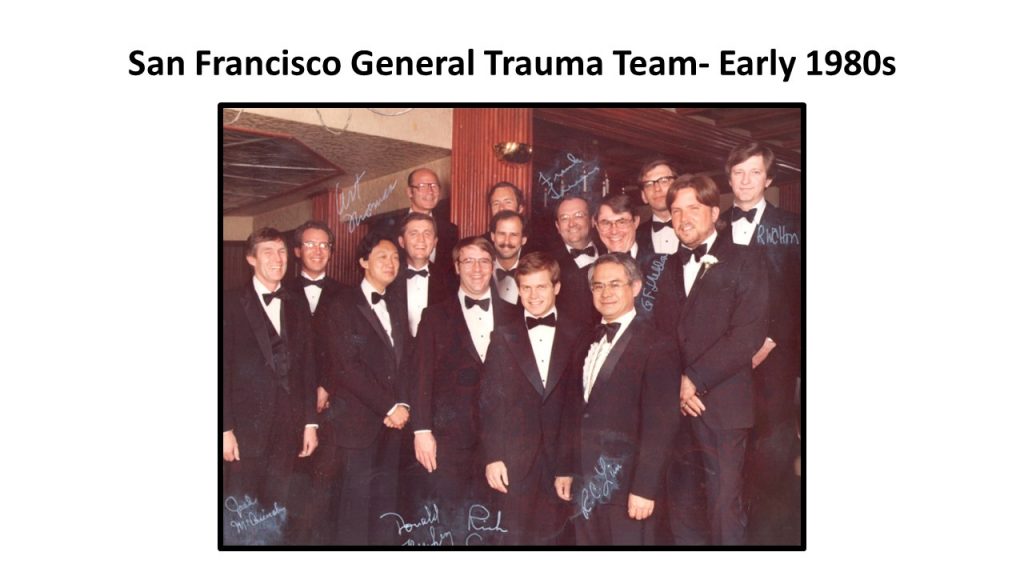

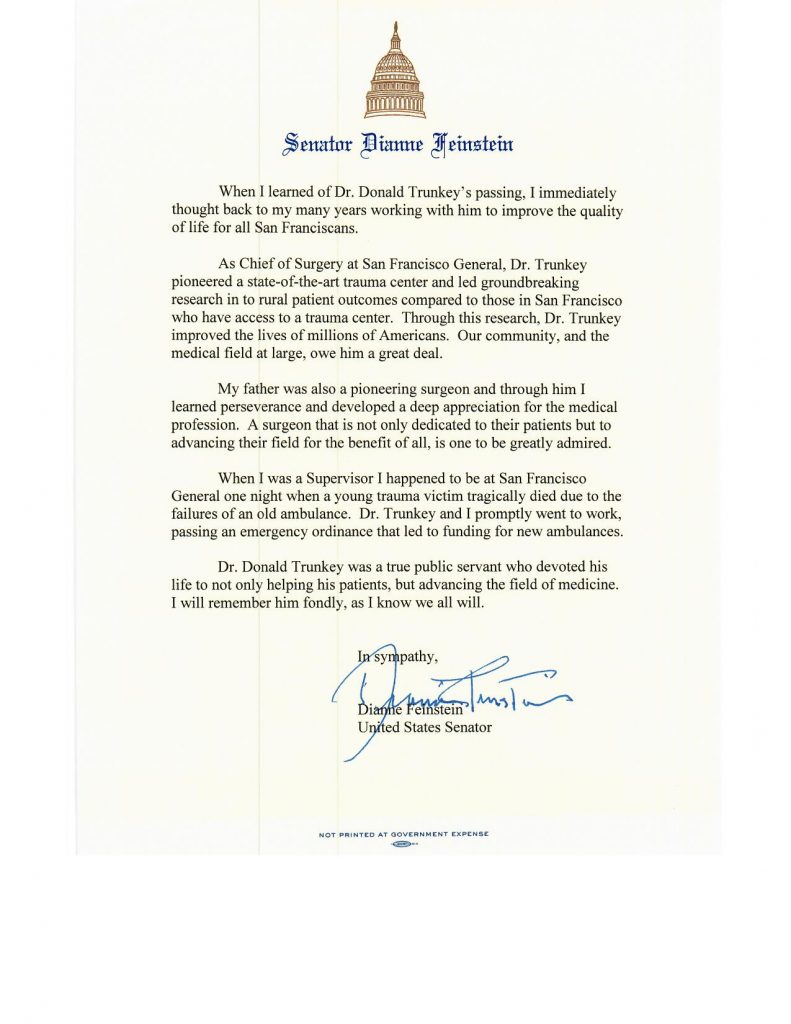

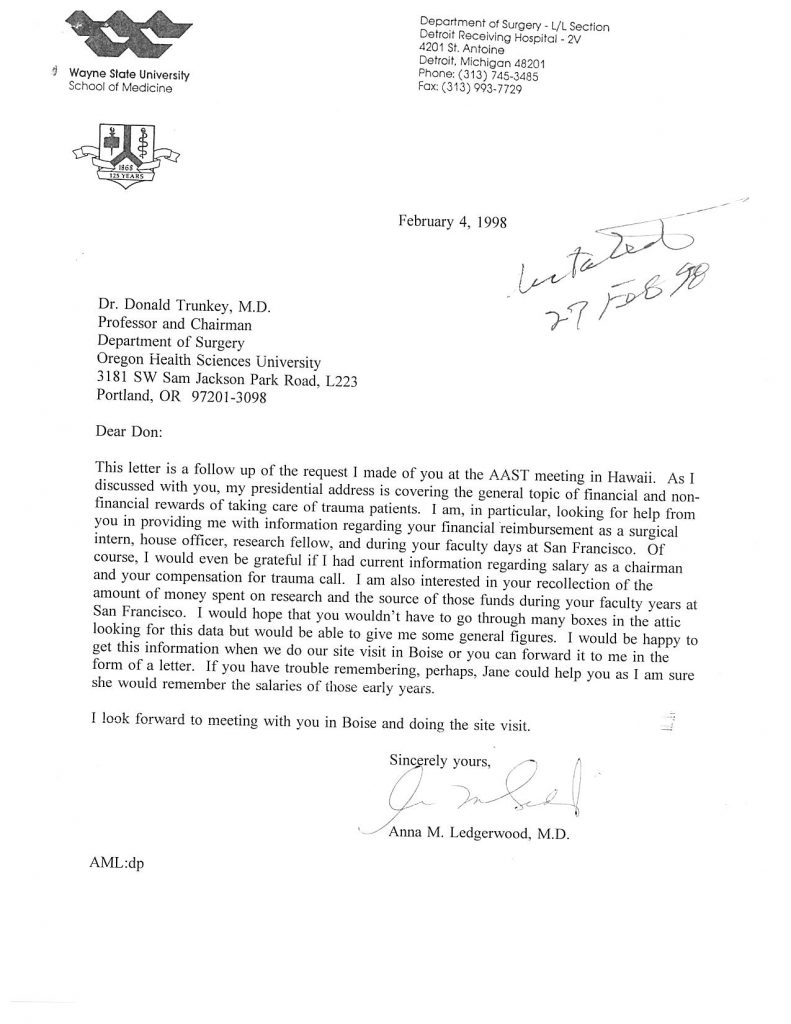

Don had a stellar career as a trauma surgeon — first through his residency in San Francisco, then becoming chairman of surgery at San Francisco General Hospital. Also a professor emeritus of surgery at the Oregon Health Science University, Don was presented the WSU Alumni Association’s Alumni Achievement Award in recognition of his influential career and contributions to medical education, surgical methods and trauma care.

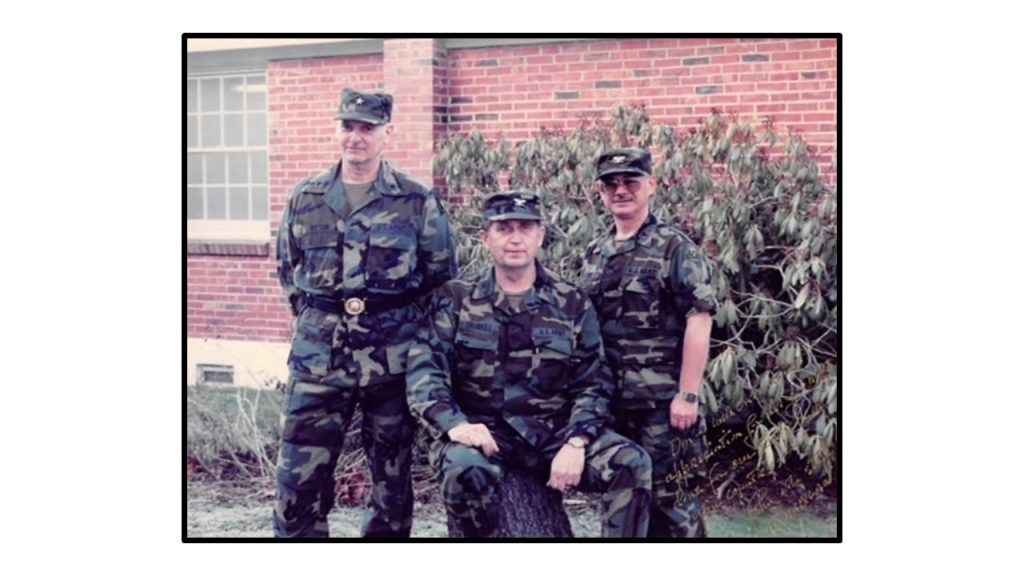

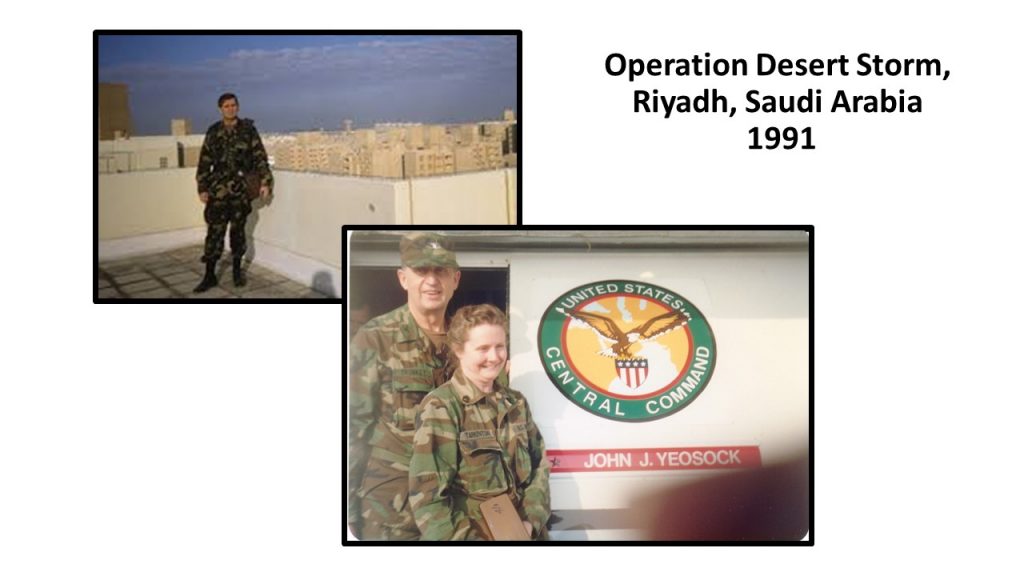

While in Portland, he also served as the head of the 50th General Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia within Desert Storm.

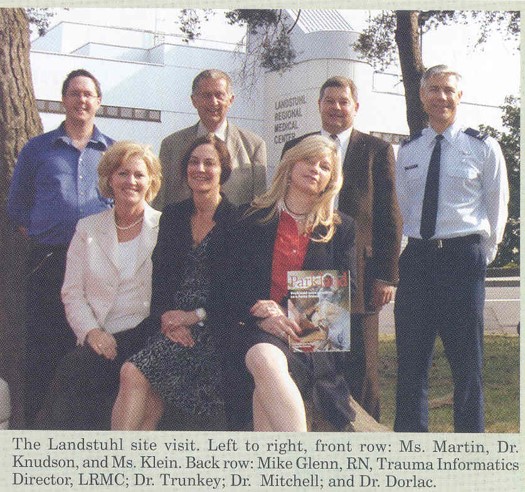

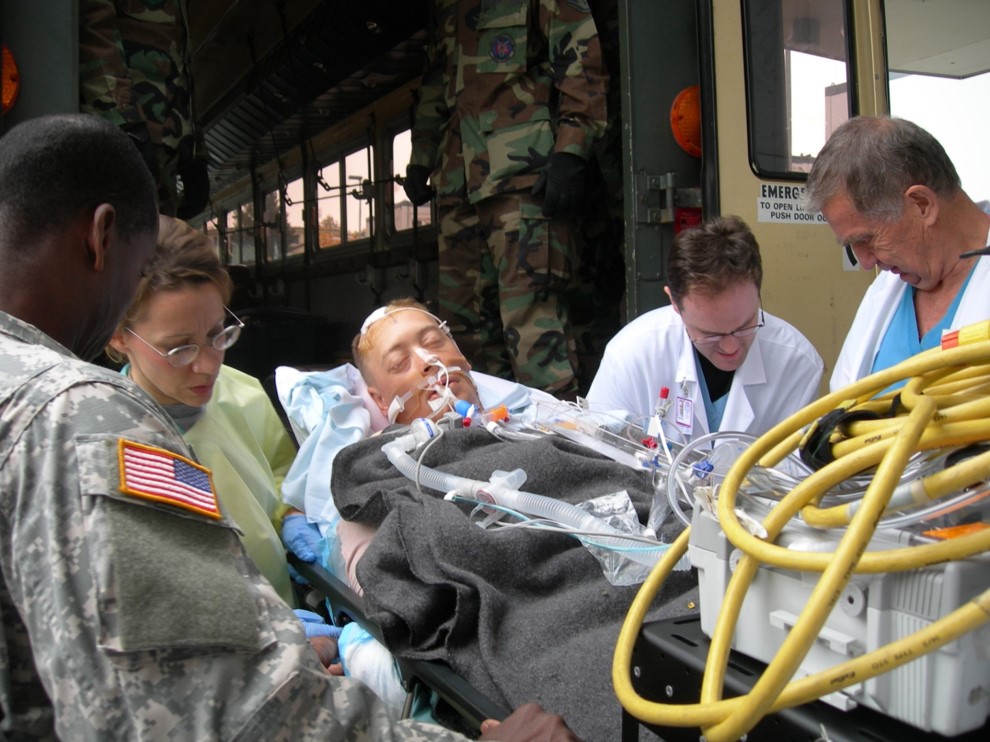

Don often volunteered in Landstuhl, Germany. While there, Col. Trunkey and Col. Daniel Cavanaugh flew Lieutenant General John. J. Yeosock to Germany for an operation. When they returned a few days later, Lt. General John J. Yeosock began the ground war. The order was given by Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr. Commander-in-Chief. Col. Trunkey was given a Bronze Star for his service.

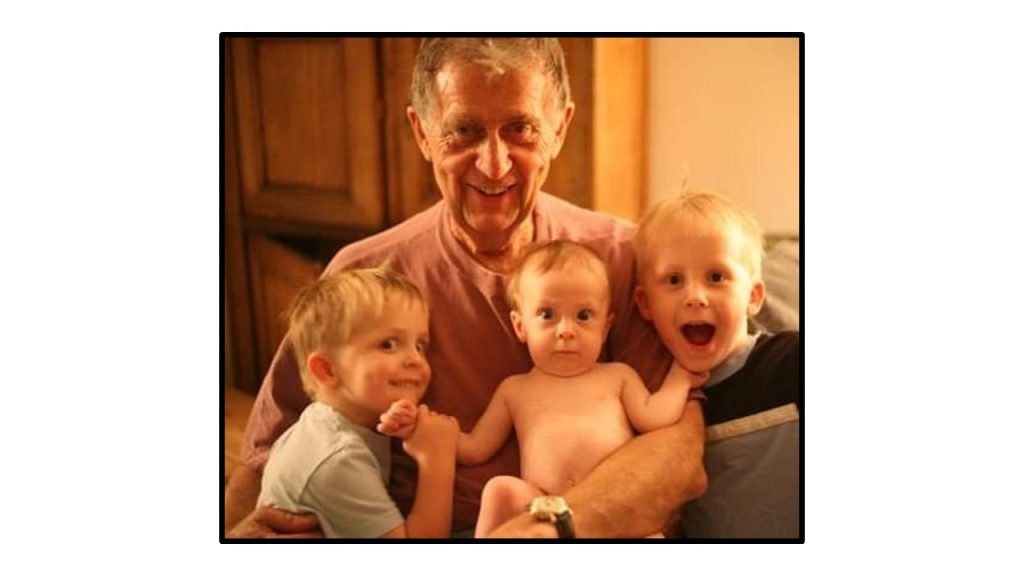

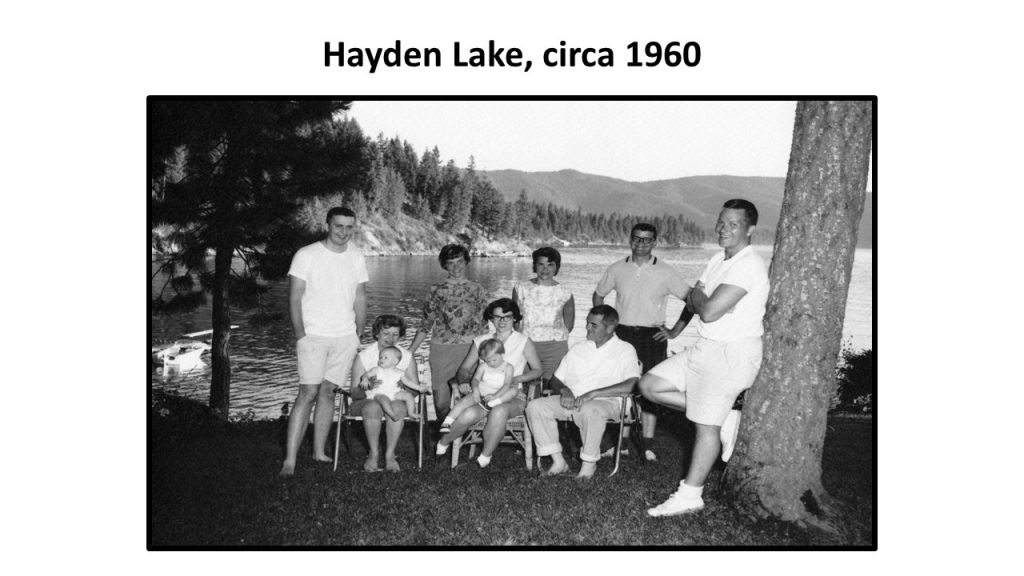

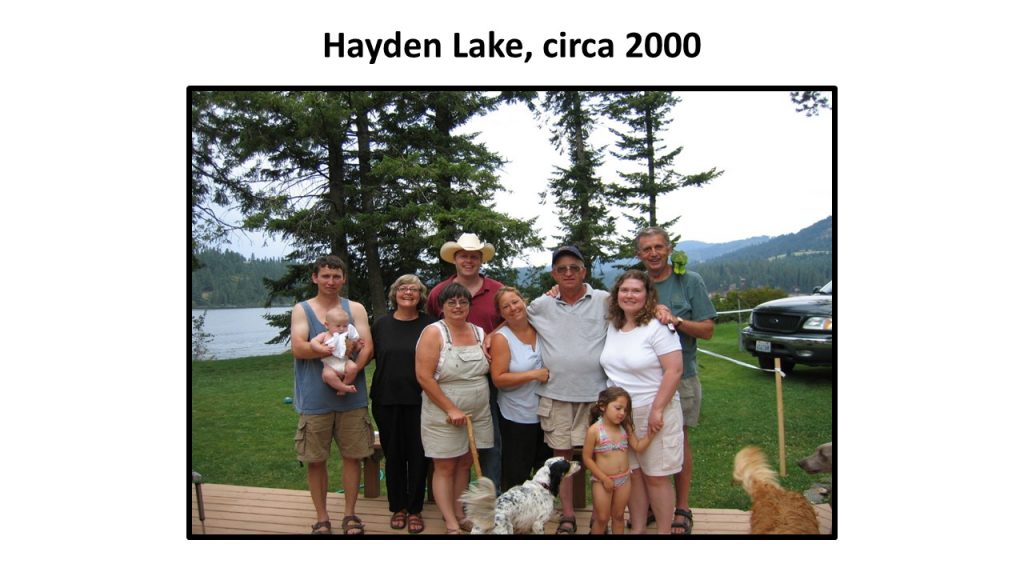

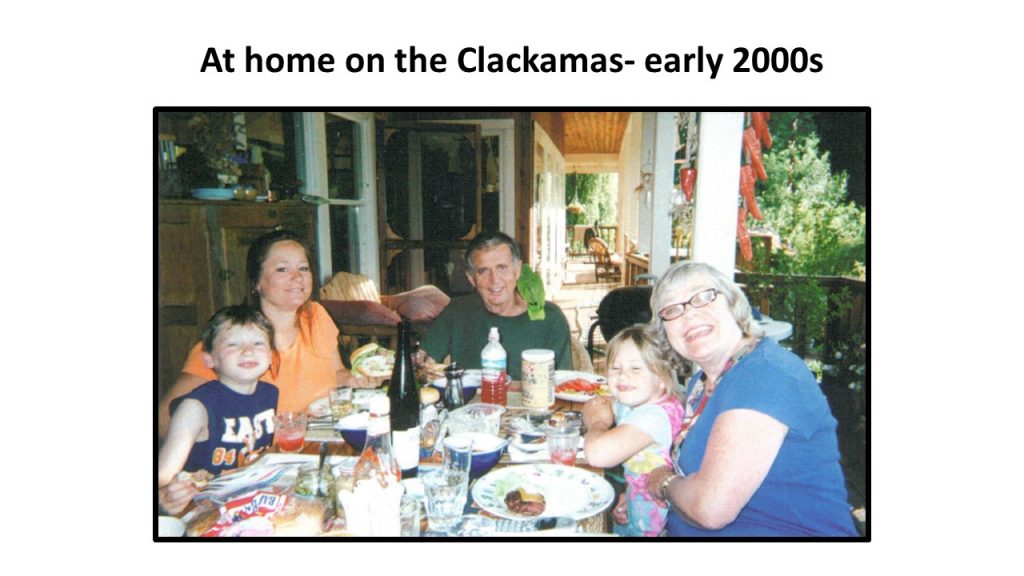

Don is survived by his wife, Jane Mary Trunkey; son, R. Derek (Kristen Hammond) Trunkey and daughter, Kristi Trunkey. He is also survived by his sister, Sandie Trunkey and his grandchildren, Ethan, Nathan, Mason, Hayden, Hayley and Harrison. Don was preceded in death by his parents and his brothers, Jay, Gary, David Roger and K.B.

A memorial service for Don will be held at a later date.

In lieu of donations, please send to Trunkey Family Scholarship, S.J.E. School Foundation. PO Box 411, St. John, WA. 99171 or the St. John Heritage Museum, PO Box 315, St. John, WA 91711.

The family also asks for donations to be made in honor of Don to the College of Arts and Sciences Scholarship Fund or the College of Education Scholarship Fund at Washington State University, located at: https://foundation.wsu.edu/give/. Checks should be made payable to the Washington State University Foundation and mailed to the Washington State University Foundation at PO Box 641925, Pullman, WA 99164-1925. Please designate on the check ”in honor of Don Trunkey, College of Arts and Sciences Scholarship Fund” OR ”the College of Education Scholarship Fund.”